Links to Other Chapters in this Series

Chapter 1: A First Lesson in Drawing

Chapter 2: Introducing the Dynamic Workspace

Chapter 3 : Words - Plastic Facts

Chapter 4 : Humpty Dumpty's Plastic World of Oneness

Chapter 5: Nature's Boundaries of Well being and Selfhood

CHAPTER 1 - First Instructions about Learning to Draw

My way of drawing is different from most people. In my early years I did a lot of drawing from static models employed by Art Schools, however most of my training comes from speed drawing of moving figures, especially ballet dancers. In my type of drawing I set myself the task of using static patterns onto paper to represent form, movement and spirit . Logically this should be an impossible task, it is however achievable through the pragmatic use of visual grammar.

Visual grammar is a young science that can be approached from various angles, these include neuroscience, consciousness studies and other grammars given to us through our studies of linguistics. My understanding of visual grammar comes from reading a wide range of books on how the mind works, as I am reading I apply my private thoughts and observations about drawing to these new idea I am reading about. This is a slow process, however my approach to drawing has changed dramatically and over the years I have developed a very individual approach to drawing and visual grammar, two subjects that are now very integrated in my mind.

My approach to drawing has been isolated and eccentric. What my eyes have become tuned to look for in a drawing is not always the same as other peoples. I cannot blame many people who do not altogether appreciate what my drawings are about, and likewise I think my approach to the mind and visual grammar will irritate many experts who already know so much more about this subject than I will ever do. I am however hoping that what I am about to write will stimulate people who have a genuine interest in art and the mind, whether they are academics or simply artists wanting to experiment with new viewpoints about how to capture the illusion of form, movement and spirit on paper.

Visual grammar is a young science that can be approached from various angles, these include neuroscience, consciousness studies and other grammars given to us through our studies of linguistics. My understanding of visual grammar comes from reading a wide range of books on how the mind works, as I am reading I apply my private thoughts and observations about drawing to these new idea I am reading about. This is a slow process, however my approach to drawing has changed dramatically and over the years I have developed a very individual approach to drawing and visual grammar, two subjects that are now very integrated in my mind.

My approach to drawing has been isolated and eccentric. What my eyes have become tuned to look for in a drawing is not always the same as other peoples. I cannot blame many people who do not altogether appreciate what my drawings are about, and likewise I think my approach to the mind and visual grammar will irritate many experts who already know so much more about this subject than I will ever do. I am however hoping that what I am about to write will stimulate people who have a genuine interest in art and the mind, whether they are academics or simply artists wanting to experiment with new viewpoints about how to capture the illusion of form, movement and spirit on paper.

What is a Drawing?

This

is not a simple question to answer. Our intuitive response might be

that a drawing is "a two dimensional representation of what we see with

our eyes", to my way of approaching drawing this is definitely a wrong answer. It took me decades to realise it was a wrong answer, but once I understood this fact my success at drawing changed dramatically for the better. In this essay I am going to

try to demonstrate, without jargon and scholarship, that drawings are

not about making physical reproductions of what the retina receives through the lens. I want to show you that drawings are to do with brain processes, processes that are many steps

removed from the physics of the light that stimulated the cones and rods at the back of the eye.

A reverse way to describe my intentions would be to say: I will demonstrate how marks, built up on the blank whiteness of a sheet of paper, create the illusion of space, time and spirit through a strategy of hijacking the hidden subconscious mental grammars (we are talking of multiple grammars that sometimes conflict). As we progress with this line of investigation we will discover examples of visual grammar that mirror the grammar of linguistics; visual nouns, verbs, adjectives, conjunctions and recursives. I will not be trying to convince you that sight is a branch of linguistics, conversely I will be suggesting that the grammar of linguistics is not a unique invention of modern evolution. Indeed there is a wide acceptance amongst those who study the workings of the mind that grammars of many sorts pervade the way the brain gives meaning to all our senses; touch, smell, hearing, taste and sight.

Drawings are illusive incomplete fuzzy things, as are the workings of the mind on which they act.

Suppose

Suppose I were to take a friend with no experience of drawing to a life drawing class. How would they tackle the problem of making a drawing? Quite probably they would work quite slowly, carefully tracing the undulations of the outlines of objects and the shapes of shadows on surfaces, measuring distances and angles and imitating what was in front of their eyes. They would want the model to sit very still while they did this, and expect her never to move for long periods of time. After a lot of practice they could perhaps become very skilled at representing what was in front of them, but they would be behaving a bit like an old fashioned camera with a very slow shutter speed. This is a respectable way to draw, and there have been many masters who produced beautiful works of art using these sorts of techniques. One thinks of the great nineteenth century masters like Jean Ingres, and who does not aspire to be as good at drawing as Ingres was?

This way of drawing comes highly recommended in Art Schools, they even claim it is the classic approach to drawing used by the old masters (A point of view I will argue with in Chapter two). I do not use or recommend this way of drawing, especially in an age where we have cameras with super fast shutter speeds.

There are some artists who are call themselves photo-realists. Their work is exceptional, and very often involves taking a photo before making the final work of art with pencil or paint.

The photo-realists are actually making maps of the light patterns that

went into the lens of the eye, they are not reproducing maps of what is

received on the retina and into the subconscious. Their way of drawing

is largely passive. They do not try to work with the mental processes

of seeing.

These artists probably believe that they are making "a two dimensional representation of what we see with our eyes". They might say "when my eye looks at a straight line I see a straight line, and what I put on the paper is a straight line". They are wrong, they are producing a map of the raw data that passes through the lens of the eye before it reaches the retina. The light that arrives at the lens contained a straight line, but straight line is projected through the distorting processes of refraction on to the concaved surface at the back of the eye, and becomes a curved line which is fuzzy at each end. By the time the light touches the retina has been physically changed into a curved line which is focused on the fovea and unfocused at its ends. Part of the line may even lie across the blind spot where there are no receptors to pick up the image. Along its journey from lens to consciousness the patterns go through all sorts of distortion processes, but what we all see is a straight line that is in perfect focus for its whole length. It is the magic of mental grammar that takes the distortion out of seeing.

If I were a teacher I would tell my friend they have a choice; they can have a passive or active approach to drawing. In the former they will be learning how to reproduce what cameras are doing, if they choose the latter they must learn to engage the processes of the mind and regard the paper as a dynamic workspace that includes time and space. When they choose the latter it is a good idea to become aware of how mental grammar works.

The Raw Data

Ingres, Jean-Auguste-Dominique

Teresa Nogarola, Countess Apponyi

1823

Pencil on paper

Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Teresa Nogarola, Countess Apponyi

1823

Pencil on paper

Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

This way of drawing comes highly recommended in Art Schools, they even claim it is the classic approach to drawing used by the old masters (A point of view I will argue with in Chapter two). I do not use or recommend this way of drawing, especially in an age where we have cameras with super fast shutter speeds.

There are some artists who are call themselves photo-realists. Their work is exceptional, and very often involves taking a photo before making the final work of art with pencil or paint.

|

| By photorealist drawing William Shank 2011 |

These artists probably believe that they are making "a two dimensional representation of what we see with our eyes". They might say "when my eye looks at a straight line I see a straight line, and what I put on the paper is a straight line". They are wrong, they are producing a map of the raw data that passes through the lens of the eye before it reaches the retina. The light that arrives at the lens contained a straight line, but straight line is projected through the distorting processes of refraction on to the concaved surface at the back of the eye, and becomes a curved line which is fuzzy at each end. By the time the light touches the retina has been physically changed into a curved line which is focused on the fovea and unfocused at its ends. Part of the line may even lie across the blind spot where there are no receptors to pick up the image. Along its journey from lens to consciousness the patterns go through all sorts of distortion processes, but what we all see is a straight line that is in perfect focus for its whole length. It is the magic of mental grammar that takes the distortion out of seeing.

If I were a teacher I would tell my friend they have a choice; they can have a passive or active approach to drawing. In the former they will be learning how to reproduce what cameras are doing, if they choose the latter they must learn to engage the processes of the mind and regard the paper as a dynamic workspace that includes time and space. When they choose the latter it is a good idea to become aware of how mental grammar works.

If my friend chooses an active approach to drawing I am ready to give him my first piece of advice "you must rid yourself of the notion that you are in competition with the camera". The camera makes a mechanical record of the patterns of light that arrived through the lens of the camera, these patterns are the raw data of sight and are far removed from the patterns that arrive in our conscious minds. By the time we see an image on the virtual movie screen in our minds

the raw data has already been coded, processed and modified by multiple modules of our brains, then reassembled and re-represented to our conscious minds. What we see on that virtual movie screen is not what the retina recorded.

The Stuff of Unconscious Thought

After the patterns of light arrived through the lens of the eye and hit the receptors on the retina, the light was converted into coded electrical pulses that were then transported along the optic nerves to the visual cortex at the back of the brain.

The coded pulses that arrive in the visual cortex are distorted fragmented information that have already been split up by the thalamus (sometimes known as the brain's relay centre), in the visual cortex the codes are reclassified and split again and dispersed to a host of specialised modules that are situated around the brain.

The specialist modules have allotted tasks such as analysing, luminesence, colour, location, movement, emotion, face and object recognition. Some of the pathways are longer and slower than others, so when the results of all this analysis is reunited with itself what started as the same information has been through other modules, some slow, some fast, and it is all out of sync.

The visual information is also integrated with other sensory information from other modalities. For instance our vision of a strawberry is enhanced by the smell, touch and taste of strawberry. Seeing a strawberry is not a simple matter, it involves colour, shape, texture, smell and taste. All this sensory stuff arrives in our subconscious minds as a mess, is distorted and made out of sync, added to sensory information from other modalities and then magically it comes up as singular images on our visual movie screens complete with smells and tastes and noises as if it were a single unified thing. Well that is how we think we experience things, but we don't. It is an illusion of how we experience things.

The visual information is also integrated with other sensory information from other modalities. For instance our vision of a strawberry is enhanced by the smell, touch and taste of strawberry. Seeing a strawberry is not a simple matter, it involves colour, shape, texture, smell and taste. All this sensory stuff arrives in our subconscious minds as a mess, is distorted and made out of sync, added to sensory information from other modalities and then magically it comes up as singular images on our visual movie screens complete with smells and tastes and noises as if it were a single unified thing. Well that is how we think we experience things, but we don't. It is an illusion of how we experience things.

The Stuff of Conscious Thought

When we experience seeing a strawberry it is a unified thing; one smelling, tasting lovely red strawberry sitting in space in a bowl on the table. These mental images, that are the stuff of conscious thought, are perhaps much more ambiguous than we believe them to be. This article, which started with a simple statement that drawing is different from photograph,y has already become bogged down with questions about how we experiance consciousness.

Consciousness is very difficult to study because it is entirely personal, and unknowable except to the individual who is experiencing consciousness. These difficulties made studying consciousness a taboo science for most of the 20th century, because the scientists of those times thought that it was impossible to apply scientific method to the unknowable and unquantifiable personal and subjective experiences of individuals.

Consciousness is very difficult to study because it is entirely personal, and unknowable except to the individual who is experiencing consciousness. These difficulties made studying consciousness a taboo science for most of the 20th century, because the scientists of those times thought that it was impossible to apply scientific method to the unknowable and unquantifiable personal and subjective experiences of individuals.

Over the last 40 years a new generation of scientists have used new techniques to open up consciousness to scientific scrutiny. They have been joined in their quest to understand the mind by individuals from a wide range of disciplines; psychologists, evolutionary palaeontologists, linguists and even artists like me say we might have something to add.

Self awareness is one aspect of consciousness that has been studied from the outside, and it is discovered to be not a single thing; self aware consciousness is distributed at centres across the brain.

Characteristic brain activities of lucid awareness

Max Planck (from the studies of lucid dreaming)

It is also obvious that conscious thought is a tiny thing when it is compared to the enormity of the stuff of the subconscious thought. It is also very unstable. When we sleep consciousness is mostly switched off, even during the day the dimmer switch is mostly switched to low, making us almost unaware of what we are seeing; for instance if you were asked what was the colour of the shirt of a man who passed you in the street, you might reply "I cannot recall". Occasionally, and only for short bursts of time during waking hours, our attention will grabbed by the sight of something really interesting, and our conscious thoughts become engaged and focused. At these moments we experience strong feelings and observe the objects that excited our interest in every small detail. But then there is an added irony. I can explain it this way: imagine you are male and have your attention grabbed by a lovely lady in a miniskirt, your awareness of

other people and objects on the periphery of your attention become even dimmer. In extreme cases he might crash the car.

Focused Attention

Focused attention distorts the world. This was well demonstrated by an experiment where a group of people were given the task of counting how many times the ball was passed by the team in white shirts. You can try this yourself, here is the video. You have to count the number of times the ball was passed within the group:

Most people are so focused on counting the passes that their inner mental world does not see the gorilla. Here is a problem for the scientist studying consciousness; they can know the raw data of sight included seeing a gorilla, and they believe people who say they did not see a gorilla. Experience is only knowable to the experiencer, but do you trust them to know what they experienced? Did they see the gorilla in their unconscious mind and discount its presence, did they see it in their conscious mind but forget about it immediately because it was irrelevant, or did neither the conscious or unconscious mind see the gorilla. How can the scientist investigate the answer to these questions wihout sharing the unknowable experience of another individual?

Perhaps this is where Art has something to offer. Drawing is about the inner world, and our drawings are a fuzzy window through which outsiders can see a little bit of the unknowable consciousness of other people. But using drawings to unravel the secrets of our inner world is still a very complex task that is fraught with red herrings and dead end alleyways.

When I am drawing I am in this state of heightened attention and alertness about the object I am trying to draw, which is one of the reasons I encourage others to draw even after they complain that they are afraid because they "cannot draw". Drawing is a bit like meditation, it heightens your awareness of the world, and by looking at your "cannot draw" efforts afterwards you will discover a lot about your inner self and how you experienced the world.

Just like the young man who was distracted by a miniskirt, the artist making a drawing focuses attention on the subject of the drawing and becomes unaware of what is happening in the periphery of their focus. This is very easy to demonstrate with drawing: Whilst on holiday in Tuscany I drew this Meadow Brown butterfly feeding on lavender, then I took a photograph of the scene I had just been drawing. See how my entire concentration was taken up by the object, a butterfly on a lavender stem, and notice how what was happening in the background has become left out from the drawing.

The photograph represents the raw data and the drawing represents, to a limited extent, what was going on in my inner mind when I was drawing the butterfly. We think the images in our head are complete, mulitcoloured and moving, like the images created by a camera, but as has just demonstrated this maybe an illusion. Perhaps it is more like the light in the fridge; when we open the fridge door the light is always on, even though the fridge light is switched off most of the day. Every time we check the fridge we see that the light is on. When I was drawing the shape of the butterfly on a lavender stem the background became very dim, maybe I am hardly aware of the colour of teh butterfly when I I thinking about its shape, but if ask myself about the colour it is there switched on and if a bumble bee had arrived the movement sensors in my eyes would have asked me to look at what was happening behind the butterfly, which is also switched on. Everything we look at with our conscious minds is always switched on in every detail; the colour, movement, smell and texture, but as soon as our attention is focused on one aspect, say the shape of the stem, the dimmer is switched back on. But just like when we open the fridge door the fridge light is on, we never see the light being switched on and off as we open the door. The illusion is that the light in the fridge is always on..

But it is possible to induce situations where we can see the light in the fridge going on and off. Here is another demo for you to try:

Place your face a few inches from the screen and focus your attention on the Smiley. After about ten seconds the fish will simply turn off, becoming the same as pattern as the background.

Memories

Memories

Drawings often mirror the experience of sight. Speaking for myself,

as someone who draws from life without the aid of photographs, I find

that my drawings are modified stereotypes. The looking part of drawing

is almost all concerned with noticing differences from the familiar stereotype, and

making the drawing is a process of recreating a stereotype with modifications. Let me explain using this image I made of two skaters:

The first stroke were the broad arch

shape of the girls back with a ball of chalk for the position of the head (which I knew from previous observation was round with a

slightly pointed chin). I also added a line of colour for the position of the outstretched arm which ran

into the arm of the male figure, then I added the skates which I guessed from deduction would be flat to the surface of the ice. By this point I had no memory of the position of the man, I

only remember he is bigger than the girl, so all this part was added

using rhythm and deduction. After this the information from the raw data of sight

was almost nothing; 99% of the information in this drawing was gleaned

from my memory banks about what humans look like. So this complex drawing, which is very individual, was created from with a few novel observations and a lot of information from my memory banks; such things as the man has two arms, two eyes looking towards his partner, guesses about how the man's weight was distributed and guesses about how his leg might have been raised. But the picture looks like Yuko Kavaguchi and Robyn ------ dancing on ice

Active and Passive Drawing : Active and Passive Sight

At the beginning of this article I explained how it is possible to draw in a passive way. I used the example of how an artist may construct a drawing from a long winded process of looking closely and repeatedly at a static model (or even a photograph), and repeated matching, referencing and re-measuring the shapes of lines and shadows against the shapes they could see on the unmoving model.

I have also demonstrated what I call active drawing, where a drawing was started using fragments of novel information from the raw data of sight which was supplements by a lot of information from memory banks. In truth both methods use visual grammar, but as we will see in Chapter two, with active drawing the visual grammar is much more in your face.

I would suggest that sight is more akin to active drawing than passive drawing. At any one time our conscious minds are much too small to focus on much information, so with active sight we recognise things in terms of stereotypes with modifications. Active drawing is really mimicking the seeing process of active sight. This is well demonstrated by cartoons which are Active drawings.

This is a well known character: Salvador Dali. If I were a cartoonist how would I draw this character for the first time?

I think I would do exactly the same as when I drew the skater. I would look at the differences between Salvador Dali's head and a stereotype of a head I hold in my memory. I would notice perhaps three key features; his strange moustache, the dark greased down hair and the long face with a square jaw. Other features, like his eyes, ears, mouth would perhaps be added from my memory banks without re-referencing to the subject.

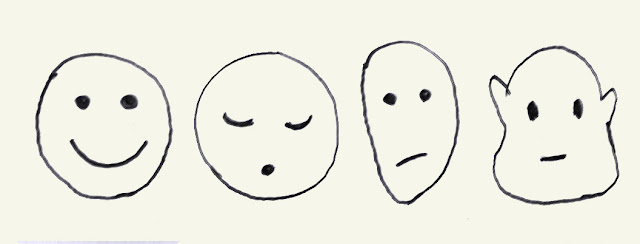

This is how the drawing is constructed

A stereotype face drawn quickly from memory

plus key features - square jaw, funny moustache and greased down dark hair)

make a recognisable individual called Salvadore Dali.

I was careful to mention that this cartoon is a first attempt. This is for a reason. I have many memory banks; one is called "stereotype man's face" and another yet to come into existance is "unique features of Salvatore Dali's face". By the time I have finished my cartoon of Salvadore Dali the memory bank of unique features of SD has come into existance. When I come to make my next drawing I can look at more interesting features of SD which can be amalgamated with the already learnt information. One thing I might notice second time round is that his hair was not greasy it was just short cropped, I might modify my undertanding of the shape of his funny moustache, and notice how his ears stick out a bit.

How about sight on that virtual movie

screen of the mind - we think the images on this virtual screen are constructed entirely from the raw

data that arrives through the lens of the eye, but this is probably

wrong. It is far more likely that the image is 99% constructed of

stereotypes with little bits of differences notices.

For instance whilst taking a walk in the Spring you might half notice white dots in the hedgerows, the subconscious mind match these to memories of snowdrops seen in past years. In the time between the raw data being picked up by receptors on the retina, and the time it arrives in the conscious mind, the data has been worked on, subverted and amalgamated with images of familiar objects already stored in the memory banks of the mind. The image we see on the virtual movie screen inside our heads are familiar because they are drawn from both the raw data and memory data. When we walked along the hedgerow did we see snowdrops or memories of snowdrops from past years?

We are inclined to believe that what we are seeing is mostly gleaned from the raw data, but looking at drawings, and the grammar of drawing (chapter two), it becomes very obvious that this is not the case. It also makes physiological sense for the brain to rely mostly on stored stereotypes because the brain is the most energy hungry organ of human body. It is calculated to be about 2% of our body weight but consume 25% of our energy intake. There is a theory that our brains gathered weight after our branch of the ape family graduated from a mostly vegetarian diet into eating high calorie meat-eaters, and this allowed our brains to grow in size. The size of our brain are already stretching our physiology to the limits of what is possible. One way to keep the brain from expanding is to save energy by not looking at the detail of something that has already been matched to stored memories and recognised, especially when the object is non threatening and not food?

Our inner vision always picks out the unusual and disregards the familiar. This is how active drawing works too.

We are inclined to believe that what we are seeing is mostly gleaned from the raw data, but looking at drawings, and the grammar of drawing (chapter two), it becomes very obvious that this is not the case. It also makes physiological sense for the brain to rely mostly on stored stereotypes because the brain is the most energy hungry organ of human body. It is calculated to be about 2% of our body weight but consume 25% of our energy intake. There is a theory that our brains gathered weight after our branch of the ape family graduated from a mostly vegetarian diet into eating high calorie meat-eaters, and this allowed our brains to grow in size. The size of our brain are already stretching our physiology to the limits of what is possible. One way to keep the brain from expanding is to save energy by not looking at the detail of something that has already been matched to stored memories and recognised, especially when the object is non threatening and not food?

Our inner vision always picks out the unusual and disregards the familiar. This is how active drawing works too.