Links to Other Chapters in this Series

Chapter 1: A First Lesson in Drawing

Chapter 2: Introducing the Dynamic Workspace

Chapter 3 : Words - Plastic Facts

Chapter 4 : Humpty Dumpty's Plastic World of Oneness

Chapter 5: Nature's Boundaries of Well being and Selfhood

CHAPTER TWO : Introducing The Dynamic Workspace

It

often comes as a surprise for people to learn that sight obeys

grammatic rules. I first came across visual grammar when I read a book by Prof. Donald Hoffman called Visual Intelligence (publ. 2000). In his book Prof. Hoffman

lists 35 rules, and he has since put up some amusing demonstrations on his

website. I think Prof Hoffman has made some profound

insights about visual grammar, however his academic approach is very different from mine.

My viewpoint does not come from academic sources, it comes through my pragmatic experience of speed drawing, which in the first chapter I called "active drawing". I chose the word "active" because it best describes the dynamic relationship between the mark making that goes on whilst a drawing is being constructed and the visual grammar of sight which determines the success of the drawing. A skilled Active Drawer learns how to place the marks that can be easily read by the visual grammar of the subconscious mind. In this chapter I will give you simplified demonstrations of these interactions at work. This chapter is a preamble for further chapters where I will examine how the paper becomes a dynamic workspace which hosts space, time and emotion, and patterns that work together to make visual nouns, adjectives, verbs, conjunctives and recursives.

All drawings start with a blank piece of paper, at this point the paper is inactive and represents a sort of nothingness.

Here is nothingness

As soon as you place your first mark on the paper it becomes reactive, which is why from now on I will refer to the paper as being a "dynamic workspace". Active drawers place themselves in the driving seat, how they decide to place the next mark will determine the character of the first mark. Let me demonstrate: suppose the first mark is a spot. As long as there are no other marks it winks "I am just a spot on a piece of paper"

Placing the second mark will sometimes add meaning to the first mark, and provide a locus for future marks. In this case the second mark transforms the first mark into the pupil of an eye. The spot is now winking back "I am an eye pupil"

If the second mark had been different it might have winked something different; in this second example the spot has started to wink "I am the centre of a flower".

Or second mark may not react in any meaningful way with the first mark - in which case the spot still winks "I am a spot" and is perhaps also saying "I am a spot which is part of an abstract pattern".

My viewpoint does not come from academic sources, it comes through my pragmatic experience of speed drawing, which in the first chapter I called "active drawing". I chose the word "active" because it best describes the dynamic relationship between the mark making that goes on whilst a drawing is being constructed and the visual grammar of sight which determines the success of the drawing. A skilled Active Drawer learns how to place the marks that can be easily read by the visual grammar of the subconscious mind. In this chapter I will give you simplified demonstrations of these interactions at work. This chapter is a preamble for further chapters where I will examine how the paper becomes a dynamic workspace which hosts space, time and emotion, and patterns that work together to make visual nouns, adjectives, verbs, conjunctives and recursives.

All drawings start with a blank piece of paper, at this point the paper is inactive and represents a sort of nothingness.

Here is nothingness

As soon as you place your first mark on the paper it becomes reactive, which is why from now on I will refer to the paper as being a "dynamic workspace". Active drawers place themselves in the driving seat, how they decide to place the next mark will determine the character of the first mark. Let me demonstrate: suppose the first mark is a spot. As long as there are no other marks it winks "I am just a spot on a piece of paper"

Placing the second mark will sometimes add meaning to the first mark, and provide a locus for future marks. In this case the second mark transforms the first mark into the pupil of an eye. The spot is now winking back "I am an eye pupil"

If the second mark had been different it might have winked something different; in this second example the spot has started to wink "I am the centre of a flower".

Or second mark may not react in any meaningful way with the first mark - in which case the spot still winks "I am a spot" and is perhaps also saying "I am a spot which is part of an abstract pattern".

Is this grammar? I am not sure. But at least this very simple demonstration illustrates that when you put marks on paper you create a "dynamic workspace". Marks react with each other.

The importance of Winking

So let's look at how we can control the winking. I am going to show you how a mark changes as it moves round a picture. Here is a smiley which is pattern that strongly winks "I am a happy face".

"I am a happy face"

If I add a random splodge, and it lands outside the boundary of the face, the new mark says nothing much. It looks like a bit of dirt or something.

"I am a happy face and there is a bit of dirt on the paper"

The bit of dirt is annoying, even distracting, but after a bit you sort of forget it is there. The "I am a Happy Face" dominates the splodge of dirt out of existence. Even when the splodge is inside the boundary of the Smiley it does not always say much, but it is more disruptive.

"I am a happy face and there is a bit of dirt ?? (or something??) under my eye"

But if you put the same dirty splodge in the centre of the Smiley something quite dramatic happens. Even though the splodge looks un-nose like, it still winks "I am a Nose"

"I am a Smiley with a nose"

It is as if the mind has decided that any mark in this position will be seen as a nose. For instance if I put a flower in this same position it winks "I am a funny flower nose"

"I am a Smiley with a funny flower nose"

and there are other areas where the splodge starts to wink.

"I am a Smiley with my tongue out"

This series of images provides a number of clues about what might be going on in our subconscious mind.

An important starting question is to ask is why do we so easily accept the Smiley without a nose? The mind clearly expects a nose to be in the gap between the eyes and the mouth, and whatever you put in that gap becomes a nose. Given this high expectation why do designers not put the missing nose there? Is it that we simply do not notice that the Smiley is missing a nose?

I can only surmise that when we look at a traditional Smiley all our attention is drawn and fixed on the eyes, the big curved mouth and boundaries of the face. These ultra strong features demand our full undivided and focused attention, and tell us strongly that this is a Smiling happy face. Would adding a nose make it be a more smiling face? I think not.

These questions and sorts of experiences are common for active drawers. When we are constructing a drawing we are placing strategic marks on the paper and interacting with our subconscious mind in the dynamic workspace.

In this drawing I made at Wiseman's Bridge last summer you can see places in the drawing where whole sections of information are left out.

Would this drawing be stronger if I filled the area between the little girl's face and her father's face? Do you miss having this extra information? How about the absence of the man's legs? Does that bother you?

Why did I leave this information out? Was it an artistic decision? The answer is that whilst making the drawing I was focusing my attention on what I was seeing, and I was drawing what I was seeing. It was not an artistic decision. I was not seeing the man's shirt, just like I was not seeing the lavender behind the butterfly or the gorilla crossing the video screen (video chapter 1).

Active drawing is mostly done very fast, and the artist is concentration on putting down as much as possible before the scene changes. In the above drawing the narrative was about the engagement between the eyes of the father on his little girl who is the main subject of this image. I was not drawing the father's shirt or legs because I never saw them. You may think how skilled is that - but ask yourself this; when you last drew a Smiley were you tempted to add a nose? If not then you were behaving just like I was when I made the above drawing. A Smiley is an Active drawing made on a dynamic workspace. When you draw a Smiley all your attention is taken up by the subject and you do not think about adding a nose because you do not see it is missing.

As we delve deeper we will discover the white patches in drawings are extremely complicated spaces, and without them we would not see movement or time.

The Missing Nose

An important starting question is to ask is why do we so easily accept the Smiley without a nose? The mind clearly expects a nose to be in the gap between the eyes and the mouth, and whatever you put in that gap becomes a nose. Given this high expectation why do designers not put the missing nose there? Is it that we simply do not notice that the Smiley is missing a nose?

I can only surmise that when we look at a traditional Smiley all our attention is drawn and fixed on the eyes, the big curved mouth and boundaries of the face. These ultra strong features demand our full undivided and focused attention, and tell us strongly that this is a Smiling happy face. Would adding a nose make it be a more smiling face? I think not.

These questions and sorts of experiences are common for active drawers. When we are constructing a drawing we are placing strategic marks on the paper and interacting with our subconscious mind in the dynamic workspace.

In this drawing I made at Wiseman's Bridge last summer you can see places in the drawing where whole sections of information are left out.

Would this drawing be stronger if I filled the area between the little girl's face and her father's face? Do you miss having this extra information? How about the absence of the man's legs? Does that bother you?

Why did I leave this information out? Was it an artistic decision? The answer is that whilst making the drawing I was focusing my attention on what I was seeing, and I was drawing what I was seeing. It was not an artistic decision. I was not seeing the man's shirt, just like I was not seeing the lavender behind the butterfly or the gorilla crossing the video screen (video chapter 1).

Active drawing is mostly done very fast, and the artist is concentration on putting down as much as possible before the scene changes. In the above drawing the narrative was about the engagement between the eyes of the father on his little girl who is the main subject of this image. I was not drawing the father's shirt or legs because I never saw them. You may think how skilled is that - but ask yourself this; when you last drew a Smiley were you tempted to add a nose? If not then you were behaving just like I was when I made the above drawing. A Smiley is an Active drawing made on a dynamic workspace. When you draw a Smiley all your attention is taken up by the subject and you do not think about adding a nose because you do not see it is missing.

As we delve deeper we will discover the white patches in drawings are extremely complicated spaces, and without them we would not see movement or time.

Location, Location, Location

Estate agents are fond of telling us that buying a property for investment is about location, location, location. A beautiful spacious house in the wrong place is worth peanuts compared to the value of a single bedroom flat in Mayfair. We might say something similar about mark placing on dynamic workspaces; the success of the mark is more determined by location than how beautifully it is drawn. This is really easy to show; let me take two marks, one looks like a nose and the other like a splodge of dirt. If the splodge is in the position where a nose should be it winks "I am a nose" very strongly, and if the nose is in the wrong place it does not wink "I am a nose" at all. All that careful observation about what a nose looks like it completely wasted!

A beautiful house in Mayfair is worth more than a single flat in Mayfair, the same applies to drawings of noses; a beautifully drawn nose in the correct location worth more than a splodge in the correct location.

The splodge shape is a nose, the nose shape is a nothing

A beautiful house in Mayfair is worth more than a single flat in Mayfair, the same applies to drawings of noses; a beautifully drawn nose in the correct location worth more than a splodge in the correct location.

This new element, lets call it "beautifully drawn" adds a new quality to our Smiley which was until now was a one horse trick. The standard Smiley is the World's best loved emoticon that is used by men and women of all ages and races to express pure happiness at the end of e-mail sentences, in this context the lack of individuality and identity was a virtue. The addition of a "beautifully drawn" nose with a broad bridge has added a strong "identity" to the emoticon. which makes it now unsuitable for use by people with narrow noses. The new element brings uniqueness and was created through a type functionality called "plasticity", ironically the emoticon gains a new side and loses its functionality. **

Plasticity

Artist do not usually talk much about plasticity, but it is one of the buzz words

of modern biology and neuroscience. Biologist will tell you that Nature builds plasticity into everything it creates, including the way the brain works. We are looking at Active Drawing, which is built on a dynamic relationship between Art and the inner workings of the mind, so it is only to be expected that we should find plasticity in the visual grammar we use when drawing.

We have already discovered that the mind is rigid and unbending in it's rules about the location of where a nose can be on the human face, but when it comes to the shape of the nose the mind gives us as much freedom as we want. Any size, shape or colour will do.

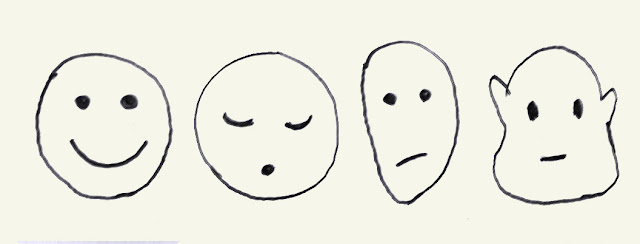

In fact the minds plasticity towards shape permits all the elements of the Smiley face to be changed, as long as the basic rules about location are not broken. So it is permissible to change the shapes of the mouth, eyes and outline of the Smiley. These are all variants of the Smiley pattern.

Best wishes

Julian

** Whilst writing this piece I realised that there is another reason about why there is no nose on the Smiley. It is not hard and fast rule, but generally speaking those parts of the body which we cannot move, like our ears and noses, cannot be used by our minds for expression. Our minds are always trying to talk with other minds, and it does this through body language. Every movable feature available, especially the eyes and soft features around the mouth are used for communication of our feelings and intentions. We also use our hands, posture and how we cock our heads. The immovable and unchangeable features cannot used for expression, thus our noses and ears are God given, immutable.

Our immutable noses, sitting right in amongst of the most moveable and expressive part of our faces, become objects of identity and individuality par excellence, which is why they are so useful for caricaturists. The Smiley is supposed to be raceless, sexless and ageless, so it makes sense not to include it as part of the icon for universal happiness. I add this point as a footnote because it is not really the subject of this chapter.

Honoré Daumier - Count Antoine Maurice Apollinaire d Argout We have already discovered that the mind is rigid and unbending in it's rules about the location of where a nose can be on the human face, but when it comes to the shape of the nose the mind gives us as much freedom as we want. Any size, shape or colour will do.

In fact the minds plasticity towards shape permits all the elements of the Smiley face to be changed, as long as the basic rules about location are not broken. So it is permissible to change the shapes of the mouth, eyes and outline of the Smiley. These are all variants of the Smiley pattern.

Is this Grammar?

I am not a linguist so I cannot answer this question authoritatively, but I can see lots of commonality between the system I am describing and the way sentences are constructed using simple linguistic grammar. For instance if we take a simple sentence like "The Cat sat on the Mat" and mess with the location of a word in the sentence, then we get a meaningless sentence "The sat on the Cat Mat".

However provided you stick with the location rules you can change the words in the sentence however you want. The words are allowed plasticity, so you can change cat to lion or dog and the sentence still makes sense. "The Lion sat on the Mat"

Another interesting thing is that we can use linguistic grammar to express ideas that we never expect to happen in the real world; The Chair sat on the Mat. This is very similar to the way we can use location on patterns to make pictures tell us stories which do not make sense in the real, like the Smiley with a flower instead of a nose.

Adding More Information

There is one more commonality between the grammar of Smiley faces and linguistic grammar; Having created a structurally correct sentence or image we can go on adding more information provided the added information is put into the correct location. So we can add hair, eyebrows, ears, moustaches and bowtie.

And we have a picture with a really strong personality.

And we have a picture with a really strong personality.

Add the same pieces in the wrong locations they have no meaning and they obliterate the original message of the image.

Likewise we can add more words to a simple sentence The sentence started as "The Cat sat on the Rug" and with additional words becomes a longer sentence with more useful information "The Blue Cat and Old Dog Sat on the Rug".

If we disobey grammatic location rules the words lose their meaning and obliterate the original message of the sentence, as in "The Cat Old sat Dog on Blue the Rug" I cannot help but be struck by the similarities in the way the two systems work.

If we disobey grammatic location rules the words lose their meaning and obliterate the original message of the sentence, as in "The Cat Old sat Dog on Blue the Rug" I cannot help but be struck by the similarities in the way the two systems work.

This chapter has looked at the structural rules governing a very simple pattern. In many ways the conclusions are banal and obvious. It is difficult for me to convey how much difference understanding this stuff has made to my approach to making a drawing. The discovery that location is more important than content was revelatory and whilst drawing I am always keenly aware of these understandings. Speed drawings are always created under time pressure, and the decisions about how to maximise the value from each successive stroke have to be instantaneous. In this context knowing that a well placed splodge has more value to the message of the drawing than a carefully described and beautifully drawn outline that is slightly misplaced, make these decisions more fluid.

In the drawing below the fingers are just rods, and at least I got the right number, but to have attempted to draw hands that were anatomically correct would have distracted my attention from the location relationships between the hands and the rest of the body....so it was a good decision not to try to draw beautiful hands.

In the drawing below the fingers are just rods, and at least I got the right number, but to have attempted to draw hands that were anatomically correct would have distracted my attention from the location relationships between the hands and the rest of the body....so it was a good decision not to try to draw beautiful hands.

It is possible that with more skill I could have done both, but at my level of skill this was as good as I could manage

The distorted Dynamic Workspace

We have looked at some of the simple stuff. This may give a wrong impression, the Dynamic Workspace has simple rules, but it has many layers of other activities that are going on simultaneous in our subconscious minds. In the drawing above the locations of the hands have been distorted by these other layers, and it will take many more chapters to explain and demonstrate this weird world of visual grammar.

Best wishes

Julian

** Whilst writing this piece I realised that there is another reason about why there is no nose on the Smiley. It is not hard and fast rule, but generally speaking those parts of the body which we cannot move, like our ears and noses, cannot be used by our minds for expression. Our minds are always trying to talk with other minds, and it does this through body language. Every movable feature available, especially the eyes and soft features around the mouth are used for communication of our feelings and intentions. We also use our hands, posture and how we cock our heads. The immovable and unchangeable features cannot used for expression, thus our noses and ears are God given, immutable.

Our immutable noses, sitting right in amongst of the most moveable and expressive part of our faces, become objects of identity and individuality par excellence, which is why they are so useful for caricaturists. The Smiley is supposed to be raceless, sexless and ageless, so it makes sense not to include it as part of the icon for universal happiness. I add this point as a footnote because it is not really the subject of this chapter.

No comments:

Post a Comment